Kansas-Nebraska Act & Pre-War Kansas Politics

Chapters

Introduction

Kansas-Nebraska Act

Seeds of Discontent

The 12th Confederate State

Missouri’s Provisional Union Government

Post War Politics

Americans in the nineteenth century would have agreed the founding fathers had created a near perfect republic. The founders however, left the tricky issue of slavery unsettled, which forced politicians to find solutions that would hold the Union together. The most important of these, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, presented a chance to settle the issue once and for all. The petition of Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state would have destroyed the equal balance with free states in the United States Senate. Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky worked tirelessly to forge a solution, both to the immediate problem, and to the future of slavery in the Louisiana Purchase. Missouri would be admitted as a slave state and Maine would enter the Union as a free state. With the equal representation of the states preserved, the southern boundary of Missouri would be the new dividing line for slavery. All new states entering the Union north of that line would be free, those from south of that line would be slave.

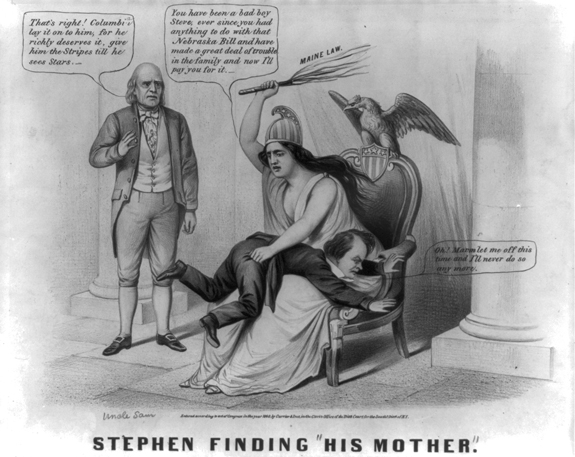

The Missouri Compromise did not become a permanent solution to slavery question, but it kept the peace for thirty years. The Mexican-American War, 1846-48, left America bitterly divided about slavery in the newly acquired southwestern territories. Once again, Henry Clay brokered a deal to save the Union with the Compromise of 1850. Settlers in the new territories would decide for themselves if they would allow slavery. This doctrine of popular sovereignty seemed to be the most democratic answer to the problem. In 1854 Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed repealing the Missouri Compromise and opening the Nebraska Territory to popular sovereignty. The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, meant slavery would be possible in the Louisiana Purchase, a thought that outraged many Northerners who considered Clay’s compromise a sacred trust.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act triggered a land rush in Kansas. Missourians were especially passionate about making Kansas a slave state. But their zeal was matched by many New Englanders, some like Eli Thayer and his New England Emigrant Aid Society, who sent equally determined free-state settlers into Kansas. Given the intensely partisan feelings, it is hard to imagine how fair elections could have been held.

In the fall of 1854, 1,700 armed Missourians poured into Kansas to elect a proslavery delegate to Congress.1 Dubbed, “border ruffians,” by the antislavery newspapers, these Missourians flooded the elections with Southern votes. The territorial elections for Kansas took place in March 1855, and reports estimate as many as five thousand Missourians crossed into Kansas to participate. Senator David Rice Atchison from Missouri reported, “There are eleven hundred coming over from Platte County to vote, and if that ain’t enough we can send five thousand – enough to kill every God-dammed abolitionist in the Territory.”2

Proslavery voters cast 5,247 ballots against the 791 from the Free Soilers in the territorial election; however, a congressional investigation later concluded that 4,986 of the proslavery votes were fraudulent.3 Intimidated by the border ruffians, Kansas politicians did not overturn the results, which led to the adoption of proslavery laws. Anyone opposing slavery in Kansas could be imprisoned, and those instigating a slave rebellion or assisting a fugitive slave could be sentenced to death.

Enraged free-staters banned together and turned Lawrence into an antislavery stronghold. Armed with “Beecher’s Bibles,” Sharps rifles transported in boxes labeled “Bibles,” the men organized the free-state party, and held an election for a constitutional convention.4 The party met in Topeka, Kansas, drew up a new constitution that prohibited slavery in the territory, and established a legislature. As historian James M. McPherson points out, Kansas had two territorial governments—one legal by fraudulent votes, and a second illegal, but representing the majority of settlers. The Democratic controlled Senate and President James Buchanan recognized the former, while the Republican House favored the latter.5

In September 1857, the Kansas Constitutional convention met in Lecompton, determined to make Kansas a slave state. Newly appointed Governor, Robert J. Walker, assured his free-state opponents that a fair and legitimate territorial legislature would be seated. The election results gave the proslavery candidates an edge, but it was soon discovered that Missourians were up to their old tricks. In one district, which had only 30 legitimate voters, 1,601 ballots were cast with names from the Cincinnati city directory.6 In total 2,800 fraudulent votes were discarded and the free-staters won the majority.

The new Lecompton Constitution included a provisional article that guaranteed a slaveholder’s right to retain ownership of their slaves currently living in the territory, but it also prohibited future importation of slaves to Kansas. Voters would later decide to include or exclude this article in the constitution. If excluded, slavery would be prohibited in Kansas entirely. Like each of the previous constitutions, the Lecompton Constitution had its opponents and supporters. Two referendums were held, each boycotted by a different party. Eventually the proslavery vote was accepted, even though it did not represent the true voice of the people in Kansas.

Heated debates took place in the Senate over the admission of Kansas, under the proslavery Lecompton Constitution. Southerners threatened secession unless Kansas became a slave state. With President Buchanan stating that Kansas “is at this moment as much a slave State as Georgia or South Carolina,” the Lecompton Constitution barely passed the Senate, and was eventually defeated in the House.7 On August 2, 1858 the people of Kansas finally rejected the Lecompton Constitution.

By this time, new emigrants had changed the demographics of Kansas. New Englanders were no longer representative of anti-slavery settlers in the territory. Instead, young families from the Midwestern states of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio had settled in Kansas and it was them, not New Englanders who made Kansas a free state. Significantly, these states had populations with both Northern and Southern roots. Missourians now confronted settlers who had arrived in Kansas at their own expense, and were looking to make a better life for their family.8

A fourth and final constitution was drafted in 1859. Newly elected delegates from the June territorial legislature met in Wyandotte, Kansas. The Wyandotte Constitution was an easy victory for the free-state voters. Surprisingly, some delegates supported equal rights for women in Kansas, but the “radical” idea was soon shot down.9 The Wyandotte Constitution met the expected opposition in Congress, but with southern states leaving the Union, the resistance soon ceased and Kansas joined the Union as the “Free State” on January 29, 1861.

Northern outrage over the turmoil in “Bleeding Kansas” had important political consequences. As the venerable Whig Party collapsed over slavery, a new one emerged, the Republicans. The Republicans vowed to respect slavery where it existed, but they steadfastly opposed its expansion into the territories. The new party ran its first presidential candidate, John C. Fremont in 1856. Fremont won 33% of the popular vote, results that highlighted the North’s stiffening resolve against slavery in the territories. By 1860, the Republicans had found another candidate, and Abraham Lincoln’s improbable victory plunged America into civil war.

Browse all collections in Politics & Government

Browse all collections in Politics & Government

- James M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001),102.

- McPherson, Ordeal by Fire, 102.

- McPherson, Ordeal by Fire, 102.

- Antislavery clergyman Henry Ward Beecher said that just one Sharp rifle would do more good than a hundred Bibles in Kansas. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire, 103.

- McPherson, Ordeal by Fire, 103.

- McPherson, Ordeal by Fire, 115.

- McPherson, Ordeal by Fire, 116.

- Jeremy Neely, The Border Between Them: Violence and Reconciliation on the Kansas-Missouri Line (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007), 64.

- Wyandotte Constitution, Kansas State Historical Society, http://www.kshs.org/research/collections/documents/online/wyandotteconstitution.htm, last visited on Feb. 26, 2009.