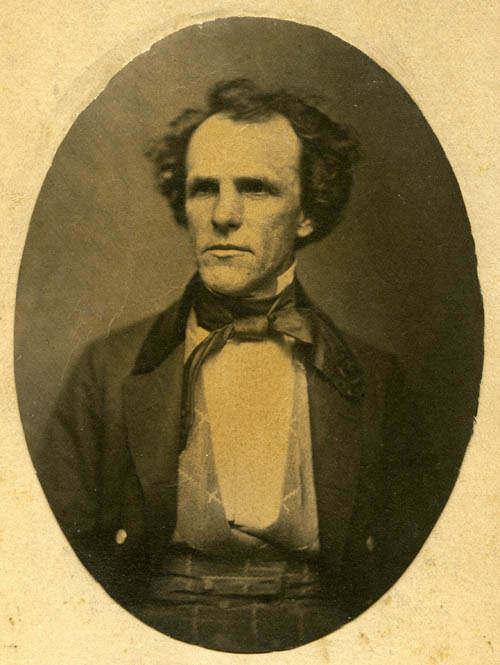

James Henry Lane Papers

Image courtesy of Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield; WICR 30806

James Henry Lane was born in Lawrenceburg, Indiana, in 1814, and followed in the footsteps of his father, an Indiana Congressman, by becoming a lawyer and Democratic politician.1 After service in the Mexican War, he served as Indiana’s Lieutenant Governor from 1849 to 1853 and then as a Congressman from 1853 to 1855.

While in Congress, Lane enthusiastically supported the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. This landmark legislation opened the territory of Kansas to settlement, and a popular vote on allowing slavery in the territory. Lane believed this act best represented the will of the American people by preventing Congress from deciding the future of the territories. Its passage embroiled Lane in a violent struggle along Missouri’s western border. Many Missourians crossed the border and cast pro-slavery votes in early territorial elections. Lane, like many other Northerners arrived in the territory determined to make Kansas a free state. Hatred grew along the Missouri/Kansas line as both sides battled for control of the territory.2 Lane organized free-state militia units throughout the territory and joined in the defense of Lawrence, the free-state capital, when it was attacked by pro-slavery forces.

Kansas became a free-state in 1861 and Lane was elected one of its first U.S. Senators. Lane used this position to build a close relationship with newly elected President Abraham Lincoln. After the attack on Fort Sumter, Lane organized the Frontier Guards, fifty-one soldiers from Kansas who were quartered in the East Room of the White House to protect the president.3 He was commissioned a brigadier general in the Union army, although in order to retain his seat in the Senate, he never accepted it. Regardless, Lane traveled to Kansas where he began recruiting soldiers and assumed command of Charles Jennison and James Montgomery’s regiments.4

Lane is perhaps best remembered for leading these troops against the western Missouri town of Osceola in September 1861. General John C. Fremont had ordered Lane to move north from Fort Scott, Kansas and intercept Sterling Price’s Missouri State Guard after the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. Instead of engaging Price, Lane led his men into Missouri on a jayhawking raid. Declaring that “everything disloyal from a Shanghai rooster to a Durham cow must be cleaned out,” Lane and his men entered Osceola on September 22.5

An officer in the Missouri State Guard described the havoc Lane’s men caused:

General Jim Lane with about 2000 men from Kansas came to Osceola. I had there two companies of about two hundred men. All raw recruits. With the few men I could keep together we fired three times on them at short range with shot guns and rifles. It was about midnight but the moon shown brightly. We retreated to Warsaw. I lost one man, and one was severely wounded. They looted and burned the town. – The fear of the Kansas men was so great that nearly all the people left Osceola and went to the country. The next day after the burning of Osceola I returned with my company to find the town still burning and the Jayhawkers all gone.

John M. Weidemeyer – Memoirs of a Confederate Soldier [1860-1865]

The raid guaranteed Lane’s repudiation as one of the most infamous “jayhawkers.” Lingering resentment regarding the Osceola Massacre stirred hatred in many Missouri citizens and made Lane a target of William Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence, Kansas on August 21, 1863. Lane barely escaped from the guerrillas by running through a cornfield in his nightshirt.6

In 1862, Lane actively recruited troops for the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, even though the enlistment of African-Americans was strictly prohibited by the War Department at that time. Regardless, the regiment was formed and saw its first combat in October 1862 at the Battle of Island Mound, Missouri. This battle marked the first time African-Americans engaged Confederate forces during the Civil War.7

Lane’s support for African-Americans did not end with enlisting them into the Union army. In Congress, Lane was an active “Radical Republican,” who called for an end to slavery and civil rights for the freedmen. On February 16, 1864, Lane addressed Congress and called on the government to enact three measures to help African-Americans, These included, arming males for military service, securing freedom for African-Americans in the Constitution, and providing them with a section of land after the war.8 Lane proposed using a portion of Texas for this purpose because of its warm climate and rich agricultural potential.

Experience further teaches that the man of color is safe from the cupidity of the white man when the tropical climate becomes his ally and protection. When he has reached the point of the tropical or semi-tropical lands, the vigor of his constitution makes him lord of the soil, so that the destiny of the whole tropical belt, in our opinion, is to pass under the future empire of the educated and civilization children of our freedmen.

We devote immense tracts of land and millions of money to a few thousand savages, who are not producers in any sense, but consumers of the nation’s wealth. It is true they have a claim on us as the original owners of the country; but have the Negroes no claim? Have not they and their fathers for centuries toiled to build up our country and our country’s wealth without pay or reward? I trust the Senate will now admit this claim, and permit us to pay, by this poor boon, a debt which has accumulated through generations past.

Despite his long career of fighting against slavery and supporting the rights of African-Americans, Lane abandoned the Radical Republicans after Lincoln’ assassination in 1865. As he embraced President Andrew Johnson’s conservative Reconstruction policies, Lane’s friends denounced his sudden of change of heart. The negative and hostile atmosphere overwhelmed Lane’s already fragile mental state and he committed suicide on July 1, 1866.9

This collection highlights Lane’s savvy political skills and the influence and power he held in the Federal government.

Contributed by the Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas

- “James Henry Lane”, Kansapedia, Kansas Historical Society, http://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/james-henry-lane/11735

- “James Henry Lane”, THE WEST FILM PROJECT, Public Broadcasting Station, http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/i_r/lane.htm

- Jeremy Neely, The Border Between Them: Violence and Reconciliation on the Kansas-Missouri Line (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007), 102.

- Jay Monaghan, Civil War on the Western Border, 1854-1865 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), 182.

- Monaghan, Civil War on the Western Border, 195.

- Thomas Goodrich, Black Flag: Guerrilla Warfare on the Western Border, 1861-1865 (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1995), 85.

- Dudley Taylor Cornish, The Sable Arm: Black Troops in the Union Army, 1861-1865 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1987), 70-78.

- James H. Lane, To Set Apart A Portion Of The State of Texas For The Persons of African Descent (Washington D.C., Gibson Brothers, 1864), The Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas.

- “James Henry Lane”, Oak Hill Cemetery, Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=10284