1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry

Chapters

Introduction

1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry

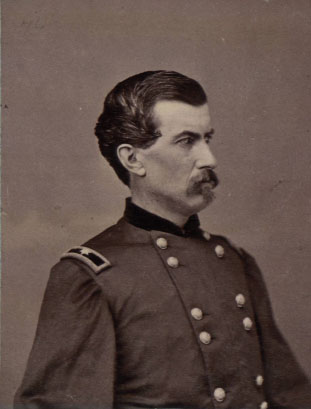

Image courtesy of the U.S. Army Military History Institute

This chapter contains language that may be objectionable to the reader. Quotes contain original language to preserve authenticity of the documents.

The political chaos surrounding Kansas Territory planted seeds of rebellion among the settlers. Bloody violence spread along the border as settlers battled over the admission of Kansas as a free or slave state. Missourians feared the strong abolitionist movement growing in Kansas and its key figurehead, John Brown.

Born in 1800, Brown was raised by his parents to revere the Bible and hate slavery. As an adult he managed several unsuccessful businesses, and helped African-Americans obtain their freedom through the Underground Railroad. In August 1855, Brown followed his sons to Kansas. After the 1856 pillage of Lawrence by pro-southern men from Missouri, Brown escalated the level of violence in the region by conducting the Pottawatomie Creek Massacre. On the evening of May 23, he and six of his followers drug pro-slavery men from their homes along Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas. They brutally murdered the men – hacking them to death with a broadsword and firing several rounds into their bodies. Brown later carried out several raids into Missouri to liberate slaves, but had little success.

Brown’s abolitionist philosophy inspired others in Kansas including the politician James Henry Lane. Lane, like Brown, moved to Kansas in 1855. He previously served as lieutenant governor of Indiana and House Representative to the thirty-third Congress. Lane was a member of the 1855 Topeka Constitutional Convention and President of the Leavenworth Constitutional Convention in 1857. He was elected one of Kansas’ two senators in 1861, and established himself as a powerful political leader. Within days of the attack on Fort Sumter, Lane organized 120 Kansas men in Washington, D.C. and marched them to the Capitol and White House. Lane’s “Frontier Guards” protected the Capitol and President Abraham Lincoln for two weeks before they were disbanded. Lincoln, at Lane’s request, appointed him Brigadier-General of Volunteers, and gave him authority to raise two additional Kansas regiments.1

Lane’s position, however, still required him to report to Gen. David Hunter, Commander of the Department of Kansas, which Lane promptly ignored. Lane had excellent success with recruiting, and on July 22, 1862 he was appointed as Commissioner for Recruiting in the Department of Kansas. Lane’s recruiting policies, however, did not follow the government’s traditional guidelines. In 1861, Lane recruited Cherokee and Creek Native-Americans and their slaves for Indian Brigades. He led raids of Kansas militia into Missouri burning buildings, stealing property and liberating slaves. Reports indicate more than 300 African-Americans were freed, and many served as cooks, teamsters and even soldiers.2 Legally, Lane could not provide weapons to the liberated slaves. But during a Senate debate in 1862, Lane declared he would tell the blacks, “I have not arms for you, but if it is in your power to obtain arms from rebels, take them, and I will use you as soldiers against traitors.”3

President Lincoln, however, was not prepared to accept African-American troops into the Union Army. He refused authority to Gen. Hunter, now in command of the Department of the South in South Carolina, to raise African-American troops, but Lane ignored the order since it had not been directly issued to him.4 On August 4, 1862, Lane appointed Capt. James Williams and Henry Seaman to enlist both blacks and whites into service, and issued General Orders No. 2. The order allowed African-Americans to enlist in the service of the United States, and created controversy for politicians in Kansas and Washington. Lane was given a direct order forbidding him from enlisting men of African descent, but again Lane ignored the message.

Lane began organization of the 1st and 2nd Kansas Colored Infantry, but had difficulties finding men to fill the ranks. He eventually resorted to his traditional tactics, of raiding towns in Missouri and capturing slaves. Within sixty days, Lane had 500 men enlisted in the 1st Kansas Colored.5 Williams was promoted to colonel and given command of the regiment. He noted the recruits demonstrated a “willing readiness to link their fate and share their perils with their white brethren in the war of the great rebellion….”6

Williams subjected his men to a rigorous training program, focusing on daily drills, dress parades and marksmanship. In late October 1862, the five companies from the 1st Kansas Colored successfully engaged a large force of Rebels at the Battle of Island Mound. The engagement marked the first time African-American troops from a northern state engaged Confederate troops as soldiers. Their victory also cost the regiment their first casualties, ten killed and twelve wounded.

Six companies of the 1st Kansas Colored were finally mustered in as a battalion on January 13, 1863. Four additional companies were added the following May. In spring of 1863, the regiment was stationed at Fort Scott, KS building fortifications. Morale among the men was low and desertion common. Williams reported to Col. Charles W. Blair, post commander at Fort Scott that, “My men have never yet received our cut of Bounty or of pay although they have now been in the Service nearly 10 Months; While other troops about us have been regularly paid.”7 He then reported to Gen. James G. Blunt that the growing “restlessness and insubordination” were a result of “long trials and sufferings” regarding the lack of pay.

I have taken the responsibility to order the details for the work on the fortifications in this vicinity to be discontinued from tomorrow morning in order to give my whole time to the discipline of the Regiment I feel that this step though irregular and unauthorized nevertheless is absolutely necessary to restrain the mutinous and insubordinate spirit which has all along manifested itself in a Small degree in the command

James Williams letter to H. G. Loring – April 21, 1863

Removing his men from work on Fort Scott afforded Williams two advantages. First, it allowed him to regain command and control of the regiment, and second, perhaps established faith among his men by demonstrating his willingness to address their concerns in regards to equal treatment as white soldiers. A few weeks later, their foraging party was attacked by Thomas Livingston and his band of bushwhackers near Sherwood, Missouri. Twenty men were killed and several were taken prisoner. Livingston and Williams negotiated terms for a prisoner exchange, but Livingston refused to acknowledge the African-American men as soldiers. A few white soldiers were exchanged, but over time negotiations for a black prisoner exchange broke down and ended with both sides killing prisoners.8 Throughout the war African-American soldiers struggled to earn respect from their Caucasian comrades, but over time their actions on the battlefield spoke for themselves.

In June 1863, the regiment received orders to escorted a wagon train headed into Cherokee Nation. The train was attacked at Cabin Creek by a force of Texas and Native-American Confederate soldiers.9 Their demeanor and calmness in battle earned the 1st Kansas Colored praise from many who fought alongside them. Gen. Blunt wrote, “They fought like veterans, with a coolness and valor that is unsurpassed.”10 And after Cabin Creek, an officer from the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry wrote, “I never believed in niggers before, but by Jasus, they are hell for fighting.”11

By the end of the War, the men of the 1st Kansas Colored were seasoned veterans, seeing further action at Honey Springs and Flat Rock in Indian Territory. The Regiment experienced its heaviest casualties during the Battle of Poison Springs, AR in April 1864. The 1st Kansas Colored, along with other Union regiments, escorted a 198-wagon forage train through enemy territory. The train was attacked by a strong Rebel contingent, and the Union troops were forced to abandon the forage train and artillery. The Federals casualties included 122 killed, 97 wounded and 81 missing.12 Afterwards, Col. Samuel Crawford of the 2nd Kansas Colored Infantry alleged the Rebels fought the Battle under a Black Flag; meaning “wounded colored soldiers were murdered on the field, as directed by the President of the Confederacy.”13

On December 13, 1864, the 1st Kansas Colored Regiment was designated as the 79th U.S. Colored Troops. The men were mustered out on October 1, 1865 in Pine Bluff, AR with 354 total casualties (188 killed or mortally wounded and 166 who succumbed to disease).

- Hondon B. Hargrove, Black Union Soldiers in the Civil War, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1988), 53.

- Hargrove, Black Union Soldiers, 54.

- Dudley Taylor Cornish, The Sable Arm: Black Troops in the Union Army, 1861-1865, (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1987), 71.

- General Hunter was appointed to command the Department of the South headquartered at Hilton Head, South Carolina in March 1862.

- Hargrove, Black Union Soldiers, 57.

- James Williams, Regimental History 1st Kansas Colored Late “79th U.S.” 1 Jan 1866. Muster Rolls and Payrolls, 79th United States Colored Infantry, AR 117, Kansas State Historical Society, 167.

- James Williams, Letter to Charles Blair. 21 Apr 1863; p. 5; Regimental Order Book; 79th United States Colored Troop Infantry, 1863-1864; Regimental and Company Books of Civil War Volunteer Union Organizations, compiled 1861-1865; Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, Record Group 94; National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.

- Correspondence between Livingston and Williams are recorded in the regimental order book.

- William’s report for the Cabin Creek engagement is recorded in the regimental order book.

- Cornish, The Sable Arm, 147.

- Cornish, The Sable Arm, 147.

- Hargrove, Black Union Soldiers, 58.

- Hargrove, Black Union Soldiers, 58.